In the Instructions to Authors, most peer-reviewed journals specify the maximum length of a submitted manuscript. Word limits typically range from 3,000 to 4,000 or even 6,000 words, depending on the type of study – original article versus technical report versus systematic review or current concepts review. Some journals include the abstract and/or references within the word limit, others do not.

Regardless, we all need to be aware of length restrictions imposed by journals. In many cases, if one submits a manuscript that is even just one word over the maximum allowed, the paper is summarily rejected without consideration. It isn’t even seen by the editor. In some cases, if one addresses the manuscript being over the word limit in a covering letter and provides sound reasons as to why it couldn’t be shortened any further, the journal may take this into consideration and send the manuscript out for review.

As a general rule, I recommend that any original manuscript being submitted for the first time should be at least 200 words and ideally about 400 words less than the maximum word limit imposed by the journal. This allows enough space to properly address reviewers’ comments and add the text they’ve requested during the revision process, without having to find words to remove elsewhere. In my experience, journals and reviewers are generally unsympathetic to using the justification of sufficiently addressing reviewers’ comments for exceeding the maximum word count.

Over the years, I’ve learned a number of strategies that have become routine for me to reduce the word count in early drafts of manuscripts provided by clients. I’ve really worked to make the scientific writing efficient – unlike my verbose, more conversational style in these blogs.

I usually look at the Results section first. A great way to save words is to convert as much data as possible to tables and/or figures, and then only highlight the main take away point(s) in the text, citing the table or figure number in brackets (see my previous blog on creating figures). Many people use extraneous words and phrases to describe their results. Be as concise as possible with your word choices.

Avoid: “Table 1 describes the preoperative characteristics of the sample …”

Avoid: “As presented in Table 2, …”

Instead, simply state the main points or preoperative demographics and cite the table in brackets:

“Complete data of 64 patients (58% female) with mean age 69.3 ± 10.2 years and mean BMI 30.14 ± 6.02 were retained for analysis (Table 1).”

“All preoperative characteristics were similar for the cohorts, with mean age 69.3 ± 10.2 years (Table 1).”

Avoid sentences beginning with “There were” or “There are”, such as: “There were no statistically significant differences between the study population and the main population [or between Group A and Group B] (Table 1).”

Instead, say: “All demographic variables for the cohorts were similar (Table 1).”

Avoid: “This association is statistically significant (p<0.001).” Instead, simply add the p-value in brackets after the main point.

Avoid (20 words): “Figure 1 shows the association between DD and RAPT as a continuous variable. This association is strongly significant (Wilcoxon p<0.001).”

Instead (13 words): “The association between DD and RAPT as a continuous variable is significant (p<0.001).”

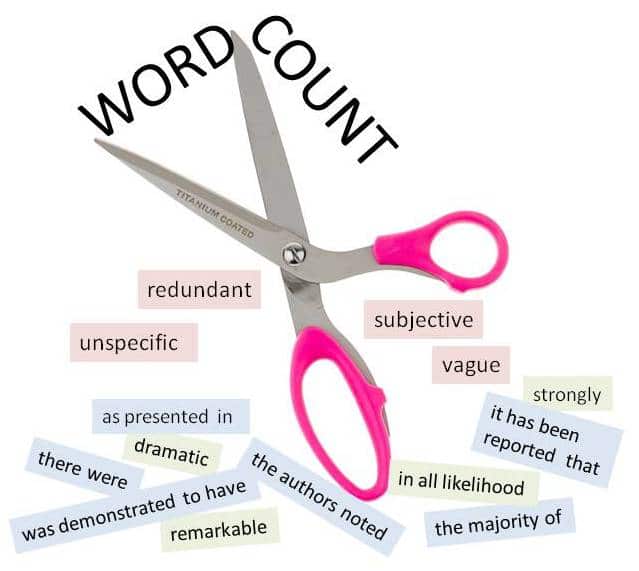

Avoid vague, unspecific qualifiers such as strongly, highly, high or low, minimal, the majority of, etc. Instead, use quantitative descriptions, such as 35/40 (87.5%) patients, 37°C, twice/day, etc. Also avoid vague words such as influence. Instead, qualify the direction with increase or decrease. Or simply provide the actual numbers.

Avoid fill words and subjective words, such as undoubtedly, purportedly, in all likelihood, dramatic, unprecedented, remarkable, and notable. Simply present the results and let the reader make up their mind about the magnitude or importance of the outcome.

When summarizing the literature in the Introduction and Discussion sections, one can edit extensively to be more succinct with the language.

Avoid phrases such as “was demonstrated (or found) to have”. Instead, simply say “had” or “demonstrated”. Delete introductory phrases such as “the authors suggested”, “the authors note”, “it has been reported that”, or “they concluded”. Instead, simply state their result.

Here’s an example of how to edit the descriptive summary of a study to make it more succinct:

Original (50 words): “In a level II prospective cohort study by Frigg et al. (33) patients receiving minimally invasive Chevron-Akin (MICA) surgery (n=50) had their clinical outcomes compared to patients who underwent open scarf-Akin surgery (n=48) with minimum 2-year follow-up. Improvements in AOFAS score, VAS pain, and radiographic outcomes were similar between groups.”

Edited (33 words): “In a prospective cohort study, minimally invasive Chevron-Akin (MICA) surgery (n=50) and open scarf-Akin surgery (n=48) demonstrated similar improvements in AOFAS score, VAS pain, and radiographic outcomes at minimum 2 years follow-up (33).”

Another example:

Original (62 words): “Sutherland et al. published several studies looking at hallux valgus from a public health perspective, including cost-utility, patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs), and wait duration prior to surgery. A level III study (25) had 95 patients complete preoperative and postoperative PROMs, and quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) were calculated by comparing the differences. There was a statistically significant difference in patient-reported health after surgery.”

Edited (34 words): “Sutherland and colleagues evaluated hallux valgus from a public health perspective in 95 patients who completed preoperative and postoperative patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) and reported a significant difference in patient-reported health after surgery (25).”

Using the lessons from above, here’s another example:

Original (44 words): “A retrospective study by Rigby and Cottom compared an “all-inside” arthroscopic Brostrom repair (n=30) to a classic open Brostrom-Gould repair (n=32). Investigators determined there was no statistically significant difference in patient satisfaction or functional outcome scores (VAS pain, AOFAS Ankle-Hindfoot score) between either technique.”

Edited (29 words): “Rigby and Cottom retrospectively found patient satisfaction, VAS pain, and AOFAS Ankle-Hindfoot scores were similar for an “all-inside” arthroscopic Brostrom repair (n=30) and a classic open Brostrom-Gould repair (n=32).”

I hope these examples will inspire you to re-examine your writing and find ways to make the text more efficient and succinct. I’d love to hear about any tricks you routinely use to make your language more concise in the comments section below.

Just shared this directly with my students (instead of Twitter this time) as I am reading the first drafts of their major lab.

Thanks, Ms De Jong, glad to hear you found my blog helpful. And yes, please share as desired. That’s what it’s here for. To make writing a bit easier for everyone.